A “very well-loved” copy of Forever by Judy Blume traveled through Juno Dawson’s sixth grade class, “like a secret little thing, passed under the desk,” she says. “By 11 years old, we’d started to put together the birds and the bees, but here it was spelled out so sensitively. It felt really truthful; a lot of Judy Blume’s stuff did. The fact that I’m remembering it now, 30 years later—it left quite an impression.”

Dawson’s 2014 guide for young LGBTQ+ adults, This Book Is Gay, has had a similar effect on readers. “What’s really lovely is I’m meeting a lot of people in their early- to mid-twenties who are like, ‘Oh my God, I read your book when I was 11 years old. And it changed my life.’ It doesn’t do anything for my ego to feel that old,” she says, laughing. “But it’s incredible.”

Another thing the two books have in common: They have both spent time on the American Library Association’s annual top 10 most-challenged-books list. According to the ALA, 729 attempted bans took place last year—more than at any time since the association started compiling a list in 2000. (For comparison, there were 275 challenges in 2015.)

Whether you blame the culture wars, social media silos, or both, it’s clear that this year we’re veering even closer to the plot of a dystopian novel, with a Virginia state legislator filing a restraining order against Barnes & Noble over the sale of “obscene” books to minors; the defunding of a Michigan library for refusing to remove LGBTQ+ titles; multiple threats of violence against library workers and patrons; and even a book-burning event targeting witchcraft-themed books following a Tennessee school board’s decision to remove Maus, Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize–winning graphic novel about the Holocaust, from a school’s eighth grade curriculum.

To mark Banned Books Week (September 18 to 24), ELLE spoke with six authors—Dawson, Hillary Chute, Nikki Grimes, Tiffany D. Jackson, Ashley Hope Pérez, and Angie Thomas—about the situation on the ground. Here, they speak out—for themselves and fellow authors; scores of beleaguered librarians and teachers; and, most of all, their beloved readers. “We can’t stress enough that the people who are most in need of access to books that speak powerfully to their experiences, or open their worlds, are the people most negatively affected by these actions,” Pérez says. “Kids who rely on school libraries; kids who don’t have a credit card to order books online; kids who don’t have bus fare to go to the public library; kids who are busy raising their own children while going to school, or caring for siblings, or working 20 or 30 hours [a week]. Those were the high school students I taught. And I write the books I write because I am thinking about readers like my kids.”

MEET THE CLUB

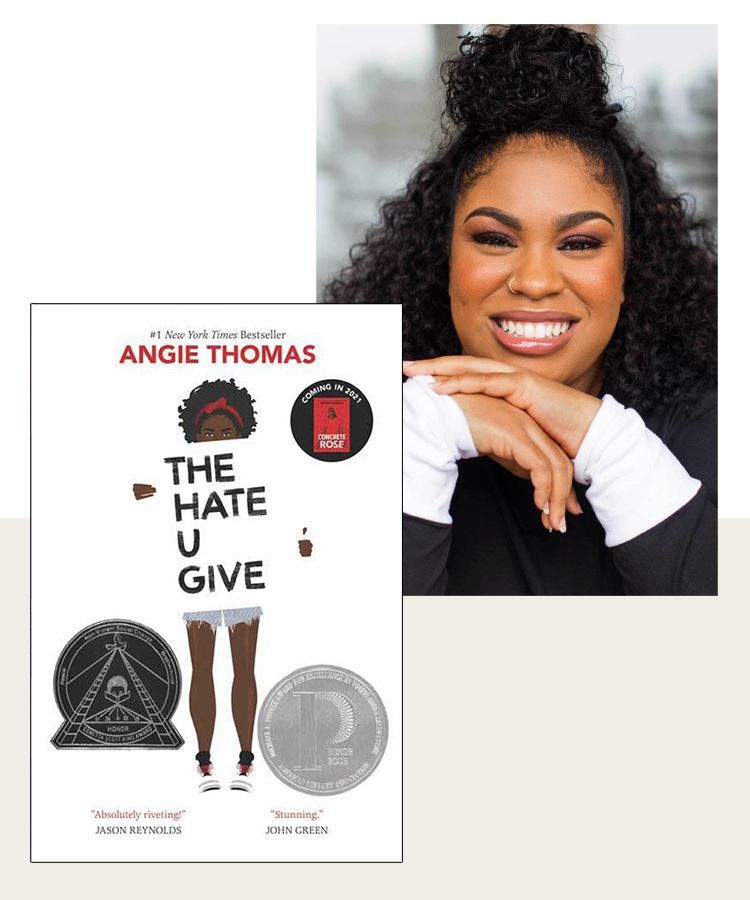

Angie Thomas

Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give follows Starr, a teen girl who witnesses her friend’s fatal shooting by a cop. It has spent 249-plus weeks on the New York Times Best Sellers list and was made into a film. The film adaptation of Thomas’s second novel, On the Come Up, about Bri, an aspiring rapper fighting to speak her truth, premieres September 23.

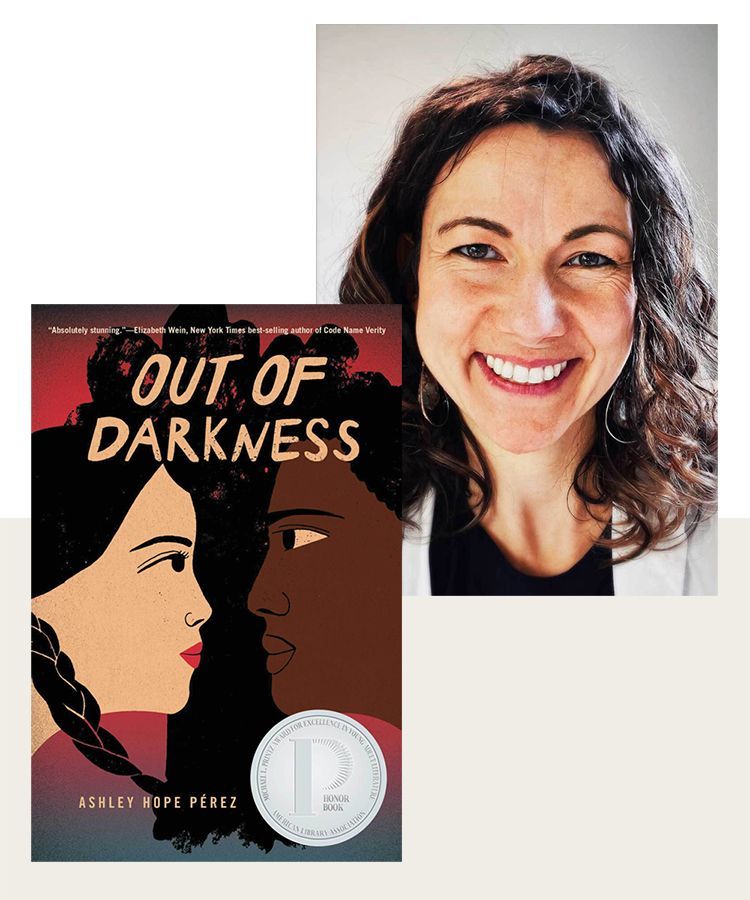

Ashley Hope Pérez

Out of Darkness

Now 10% Off

Ashley Hope Pérez’s Out of Darkness, a historical novel about a relationship between a Mexican American girl and an African American boy in 1930s Texas, was a Printz Honor Book and Tomás Rivera Mexican American Children’s Book Award winner. It is the ALA’s fourth-most-challenged book of 2021, for “depictions of abuse” and “sexually explicit” content.

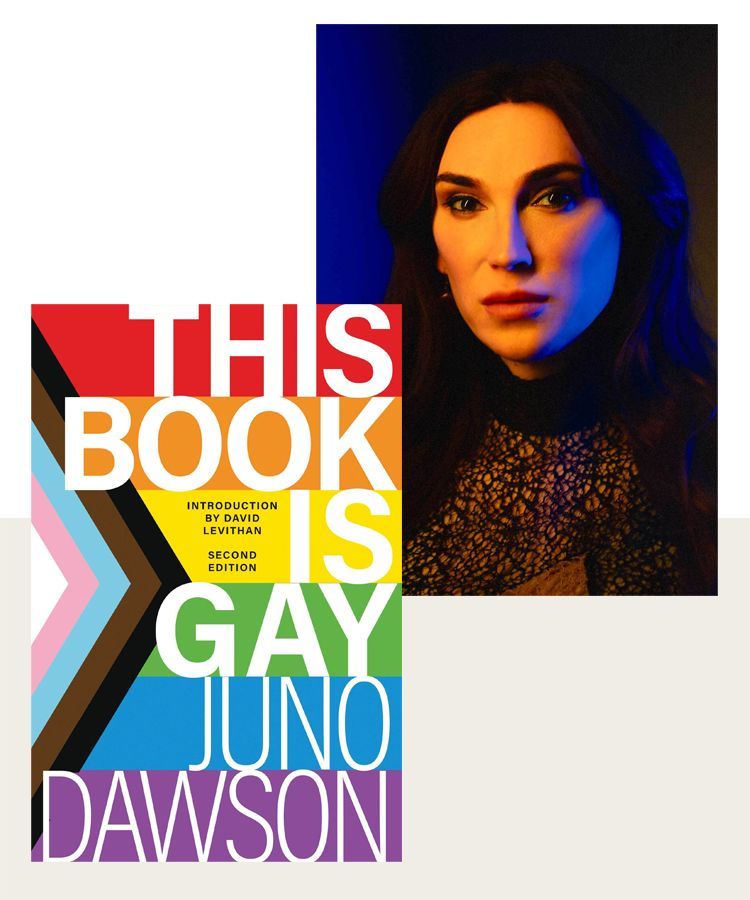

Juno Dawson

Juno Dawson’s This Book Is Gay, a guide for young LGBTQ+ adults, is the ALA’s ninth-most-challenged book. What’s the T? (a follow-up guide for trans and nonbinary teens) is out now, as is Her Majesty’s Royal Coven, a novel for adults and a number one on the UK’s Sunday Times best-seller list.

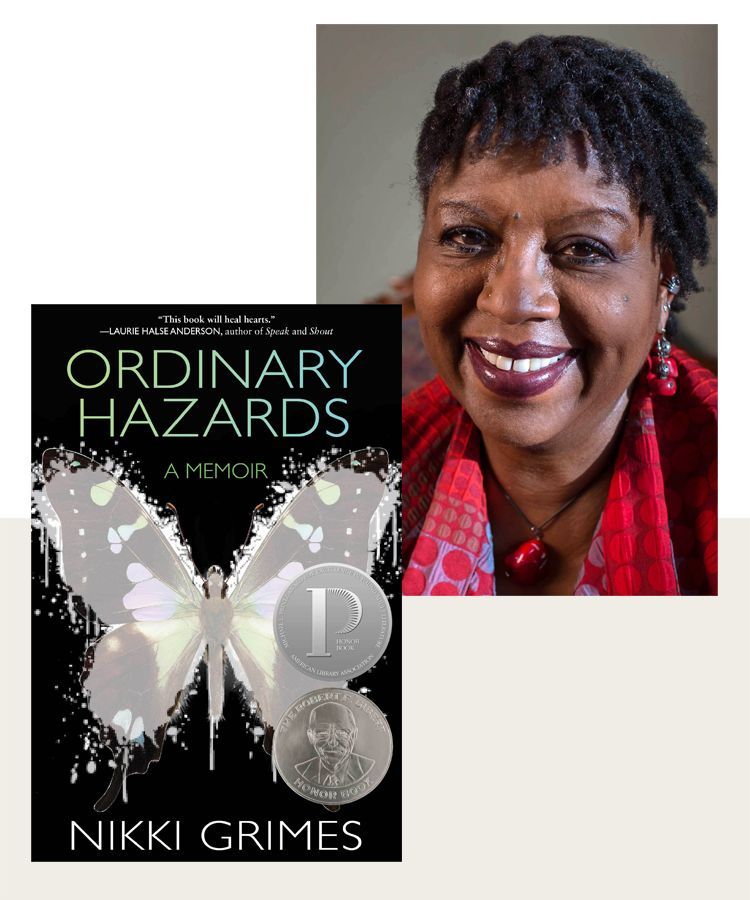

Nikki Grimes

Ordinary Hazards: A Memoir

Nikki Grimes’s memoir, Ordinary Hazards, details the harshness of her childhood, and the way reading and writing sustained her. Her novel Bronx Masquerade won the 2003 Coretta Scott King Author Award. Garvey in the Dark, a novel in verse (and follow-up to Garvey’s Choice), is out October 25.

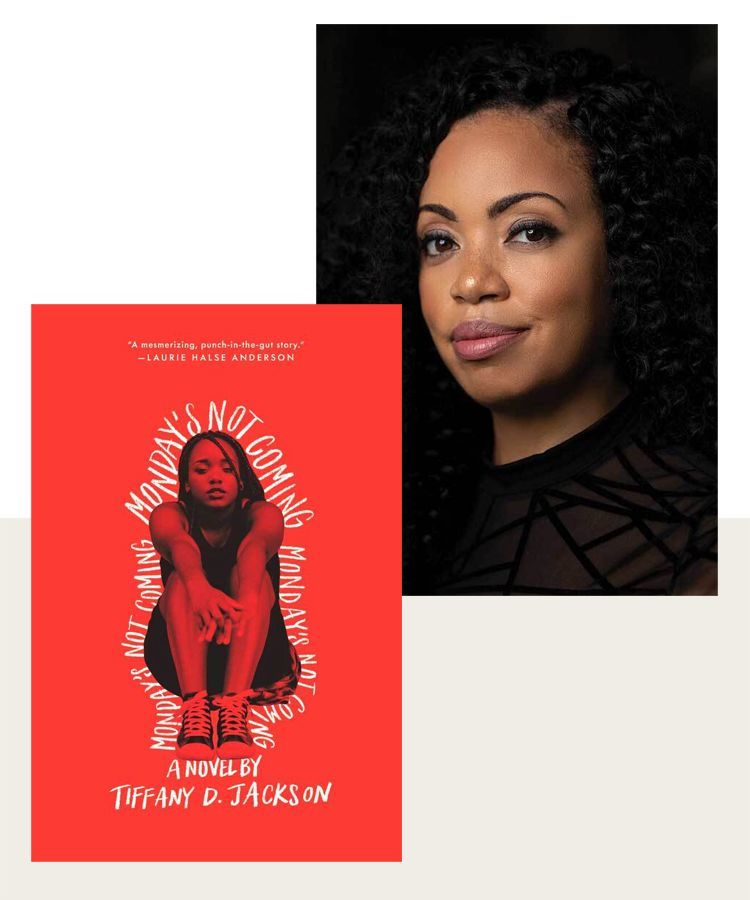

Tiffany D. Jackson

Tiffany D. Jackson’s Monday’s Not Coming centers on a young Black girl whose best friend goes missing, and has been cited for “sexual content.” Her latest book, The Weight of Blood, a horror novel, is out now. Whiteout, a YA romance she cowrote with Thomas and four other authors (Dhonielle Clayton, Nic Stone, Ashley Woodfolk, and Nicola Yoon), is out November 8.

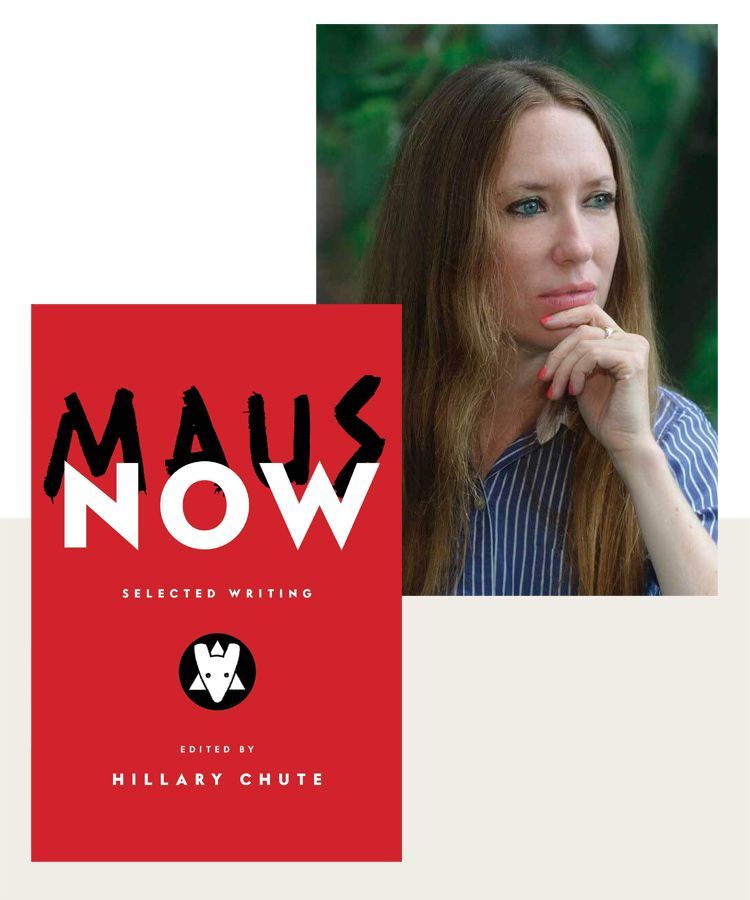

Hillary Chute

Maus Now: Selected Writing

Hillary Chute’s Maus Now, a collection of essays she edited based on Art Spiegelman’s landmark work, is out November 15. The literary scholar and expert on comics and graphic novels, including many by challenged authors, advised on the documentary film No Straight Lines: The Rise of Queer Comics.

ON ERASURE

NIKKI GRIMES: At my age and state in life, I had no plans of becoming an advocate, but this is a fight that found me. I finally write the story of my life, the one I consider the single most important story I have to tell [Ordinary Hazards], so that readers who are in the darkness of their own lives can see that there is light at the end of the tunnel—and this is the story you’re going to ban? You’re saying this book is inappropriate for children, and it’s the story of my childhood, so there’s a feeling of erasure. I am not about to be erased, or let any child who has those kinds of experiences be erased. So it was like, “Oh yeah, we’re going at it.”

ANGIE THOMAS: America has a history of telling young Black kids that the things you enjoy, the things that speak to you, are wrong. If you look at hip-hop—not just the music, but the culture—people wrote it off before it became mainstream. It was this, it was that, it was violent. But it was just talking about what was actually happening in communities. Now we’re having this same conversation about books that young Black kids identify with.

JUNO DAWSON: I’m hearing from librarians that This Book Is Gay is being challenged in places that are full of LGBTQ+ youth. And my big worry is that these young adults are internalizing that conflict, learning by osmosis that there is something about them that is worth debating or controversial. It feels as if the resistance comes from the [desire to] uphold the notion that there is an ideal way to be, and that being LGBTQ+ is a worst-case scenario.

ASHLEY HOPE PÉREZ: I ask the folks who feel their kids don’t need these books because their life is tidy, “Do you want your young person to be successful in a diverse society where they will encounter people who’ve had all kinds of experiences? Do you want them to be ready to excel at the flagship university in your state?” Young people who walk into my world literature course at Ohio State University who have never read thematically challenging material are not well equipped to do the work. And they’re not well equipped to relate to their peers. These texts matter for the kids for whom the experiences they depict are resonant, but they also matter for that opportunity to imagine other experiences.

ON HISTORY

AP: Out of Darkness is set in the 1930s, but it speaks to now because current racialized violence has roots in that time, and earlier. The folks seeking to remove important books from schools are trying to take away the opportunities to critically examine our history and the experiences that shape young people’s lives now.

HILLARY CHUTE: Maus Now was in production before Maus was challenged in Tennessee, and before January 6, 2021. And I would say the central argument of the book is that the past is not past. I was keeping a file called “Anti-Semitism Now” while working on Maus Now, and I couldn’t keep up. There was the shooting at the Tree of Life Congregation synagogue in Pittsburgh; the white supremacists in Charlottesville, shouting “Jews will not replace us”; the January 6 rioter wearing a “Camp Auschwitz” sweatshirt. And I had this horrible feeling—this horrible knowledge—that anti-Semitism was always there; it was only just becoming dramatically more legible, encouraged even. And that’s an incredibly depressing thing, but it also showed me the importance of Maus, a book that resists fascism. I wanted that reading, that context, of Maus to be clear.

JD: We need to learn from history—that from societal strife, fascists thrive. We saw this in the rise of Nazi Germany. We had the big crash of 2008, and COVID made everything worse. It feels very clear to me that the reason families and individuals are struggling has nothing to do with minority groups. Trans women are not the cause of your financial woes. With the energy people spend on trying to get these books banned, imagine what they could do if they were feeding the homeless or starting a warm-clothing drive ahead of winter.

If you can get any of them to actually read the book, then they’re like, Oh…oh.

ON CONTEXT

NG: Most of the people engaging in book banning have never read the books. They’ve been given a script to follow—a few lines here and there, and they’re off and running. If you can get any of them to actually read the book, then they’re like, Oh…oh.

AT: I recently had a woman reach out to me on Twitter whose dad is a retired cop. He was part of what I call “The Facebook Book Banning Brigade.” Her dad was furious about The Hate U Give being in a local school. He was like, “Look at how many f-words are in it!” So she asked him to read the whole book and not just pick sections out. So he did and came back to her and said, “Wow, I’m glad you told me to do that. It really opened my eyes and changed my perspective. This book needs to be in schools.” I wish more people would actually read the freaking book! Don’t judge a book by its cover, and don’t judge The Hate U Give by its f-bombs.

ON SELF-CENSORSHIP

TIFFANY D. JACKSON: My books have been classified as CRT [critical race theory], but my latest novel, The Weight of Blood, is the first one where I’m actually addressing race. It’s a horror novel, set at a school’s first interracial prom with a girl who has been passing for white. It’s an homage to Stephen King’s Carrie, and there are some very violent scenes in it. And there are some parts where I dialed it back, simply because I’m exhausted. This is the first time the public has dictated some of the content. I hate to feel like I am folding to a disgusting machine, but sometimes you have to do things for your own mental health.

AT: I had a similar experience with the book I’m working on. It’s a middle-grade fantasy novel, but it doesn’t shy away from talking about real-life trauma. There’s a scene that discusses Emmett Till, and for a moment, I wondered if I should even say that Emmett Till was a Black boy who was killed by white men for supposedly whistling at a white woman, since that might get this book labeled as CRT. I had to check myself because this is history, and I would be doing Emmett Till a disservice if I didn’t discuss the things that led to his death. And if that makes somebody uncomfortable, if that makes somebody say, “Oh, this is CRT,” then I want them to look stupid. You wonder, At what point will people be okay with uncomfortable truths?

JD: This Book Is Gay came about because my publisher felt there was a gap in the market for a book about sex and relationships for young LGBTQ+ people. And at the time I was really broke [laughs]. I was going through the worst time of my life: I got dumped by my boyfriend; I realized I was trans; my life was a mess. Later, the transphobia situation in the UK became worse, and I felt powerless, even as a very privileged trans person. So I thought, Maybe it’s time to do a follow-up to This Book Is Gay, because that’s the one thing I can do. What’s The T? is much, much more PG. There are no swear words whatsoever. I have no doubt in my mind that people are going to try and challenge it, but we wanted to make it harder to do so. It feels like a battle. Occasionally I get a poison-pen email calling me a pedophile and a groomer and all kinds of horrible things. But the people who are dealing with all this nonsense by and large are the booksellers, teachers, and librarians. I only see a fraction of the true horror when someone tags me in a tweet. So I’ve been very mindful while writing that there is going to be some poor librarian or bookshop having to really go through it. I guess I’m trying to make life as easy as I can for them.

AP: I’ve received a lot of hate mail, a lot of harassing messages and phone calls. I had to take my profile down from my university website and my name off my door. When they couldn’t find my phone number, they would just dial down the list of my department. But one of the things that helped me was making those things public, saying, “This is the hate letter I received in my mailbox today.” Because it is really valuable to hear, “That’s disturbing,” or “There’s nothing about this that’s about dialogue.” It helped me to keep from feeling like I had to hold all of those buckets of slime on my own. While some of this is happening because of online spaces and how quickly things spread, there are also some supports that wouldn’t exist for us without the kind of interconnectedness we have online.

TJ: Last year, a school district in Virginia had a board meeting with huge printouts of my book. It was covered by Tucker Carlson. People were texting me about it and my email inbox started to get flooded. My aunt passed away that same week, so I kept quiet because my family was in mourning. I didn’t even go to the funeral, because I was worried something would happen and I would detonate. It killed me not to say anything. Now I feel better suited to have these conversations. But one of the things I’ve realized is that we Black authors are spending so much time addressing all of these problems that we don’t get enough time to spend with our books. It’s very important to say something, but I refuse to make it my full-time job.

AT: It’s emotionally taxing. I’ve had to disconnect from it so I can work on the next thing and still have the joy that comes with writing. I don’t want to sit here writing this book feeling like there are a thousand eyes of white people watching over my shoulder to make sure I’m not writing something that makes them uncomfortable. So I mute my name on social media. I ask people not to tweet me the articles. I don’t deal with it, because if I do, I’m never going to get the work done, and that’s going to accomplish exactly what they want.

ON THE “BAN BUMP” MYTH

JD: The first time I was challenged, some of my friends were like, “Oh my God, you’ll be a best-seller now.” But (a) I wasn’t, and (b) it just made me sad. It felt like two steps forward, one step back, because how amazing was it that a book like This Book Is Gay could be published? I would’ve killed to have that book when I was a kid. As a queer teenager growing up in rural Yorkshire, I felt like an abomination, like if I told someone, I’d be made homeless. But for all that progress, there are still people saying, so vocally, “Ban this sick filth!” I just despair for these kids. In some ways it hasn’t gotten any better since the ’80s. We’re still having the same conversation, and it’s just endlessly frustrating.

NG: There was a teacher excited about teaching my book Bronx Masquerade, so he raised money and bought 200 copies for his ninth graders. Once the books arrived, he was told, “You can’t teach that book.” And this is why I’m so upset by the messaging that having a banned book is a badge of honor, or being told, “You’re just going to sell more books.” I’m like, “Hold on. It’s not even about that.” Some books will sell; others won’t. But the bigger issue is that access to these books is being removed. I don’t care how many books I sell. If my readers don’t have access to them, what is the point?

AP: It’s really easy to break it down. Books that are already super widely available and highly visible are going to sell more copies if they’re banned. But the vast majority of the 850 books Texas state Rep. Matt Krause wants to ban have never been on a best-seller list. The most important market for young adult and children’s literature is school libraries. And you’re creating a situation where a librarian is going to hesitate before making a book purchase. They know it’s highly regarded material that’s of value to kids, but it’s by an author they’ve seen on one of these lists, which might attract controversy. In the vast majority of cases, the argument to remove books won’t hold up. But it doesn’t matter, because the damage is already done.

NG: There are teachers who have been fired. So they’re thinking twice, like, “I’d like to teach that book, but…”

AP: “…not this year.” Book bans were once a local issue. But this is completely orchestrated and viral in nature. If you go to the Facebook pages of these various groups, they’ll tell you things like, “This is what you can say” and “This is what you shouldn’t say.” Don’t mention race. Focus on the “sexually explicit” material. Don’t talk about gender identity. What they say are their concerns are not actually what it’s about. It’s about policing identities.

THE GOOD NEWS

HC: The thing that’s been really moving to me is seeing teachers rally to collect money to buy books, or students starting petitions and book clubs. Or the Brooklyn Public Library’s Books Unbanned initiative, in which students in districts where books are being banned can check out books for free and get electronic access. There’s something heartening about people being galvanized to respond.

TJ: Monday’s Not Coming is about missing Black girls. The best responses have been from students and teachers who say, “There is a Monday in my class, and now I know to pay attention” or “I haven’t seen this girl in a couple of weeks—let me sound the alarm.” This story is reminding people not to let Black girls fall through the cracks. I will take all the heat if one Black girl is saved.

NG: I recently heard from someone who’d just finished reading Ordinary Hazards. They were reading it at work, and a coworker caught them crying. They said, “You broke my heart, and then like every great poet, you fixed it.”

Interviews were condensed and edited for clarity.

BOOK CLUB RECS:

Five more bafflingly banned books to add to your nightstand.

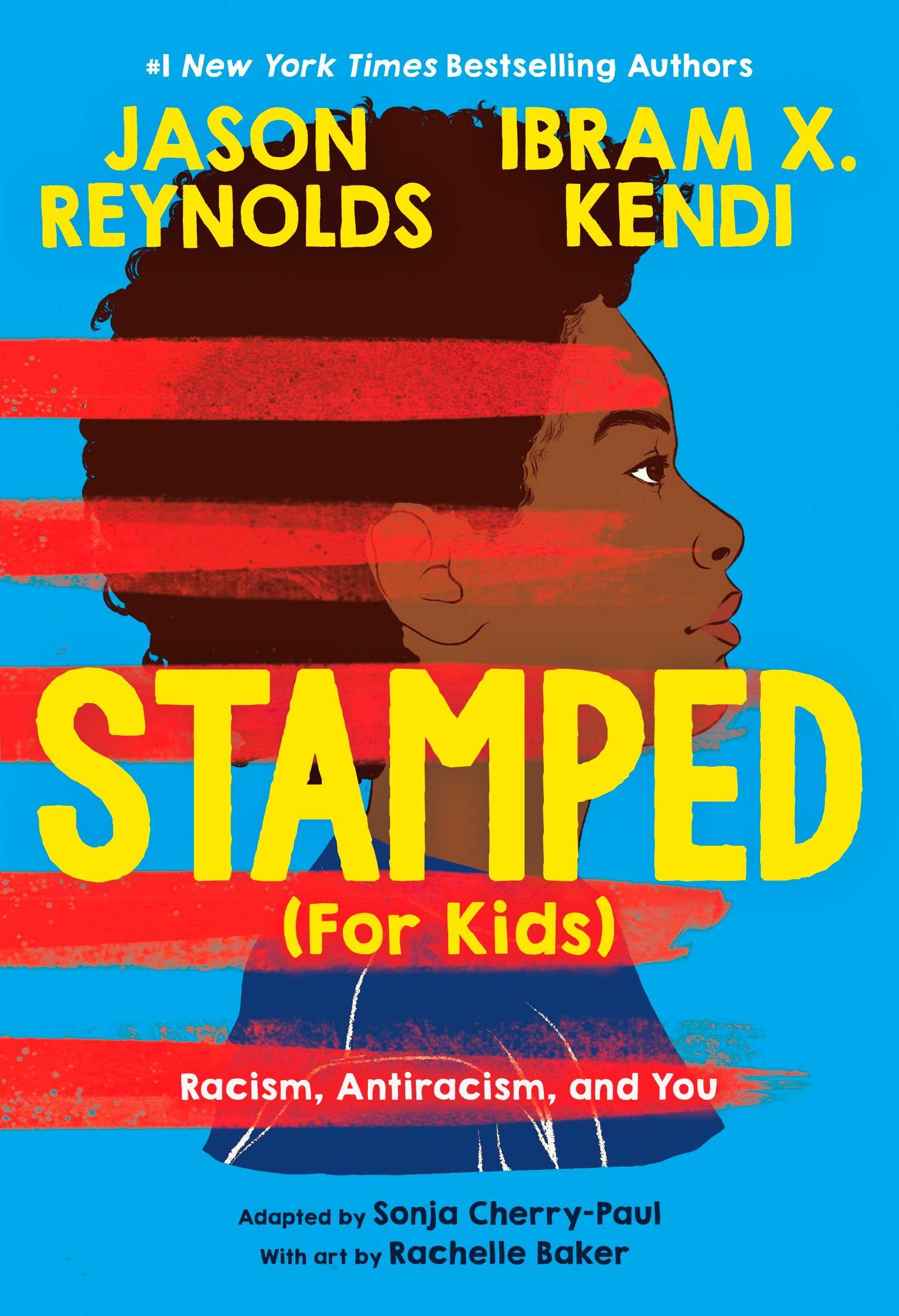

Recommended by Angie Thomas And Tiffany D. Jackson

Stamped (for Kids): Racism, Antiracism, and You by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi

“I find it fascinating that we’re challenging facts now—literally things that happened,” Thomas says of this essential tome on the history of racism.

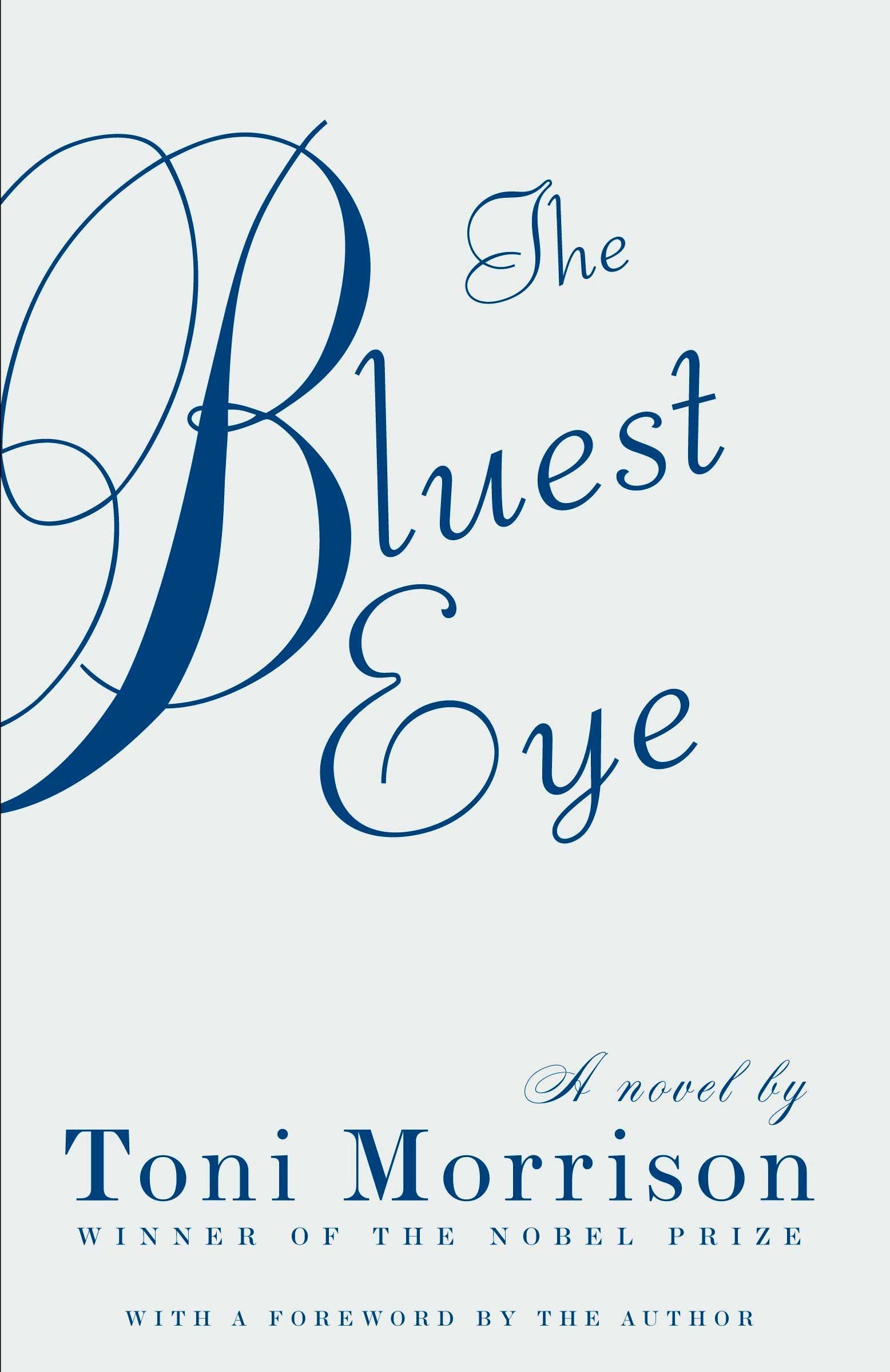

Recommended by Hillary Chute

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

“It’s decimating that this book about Black girlhood by one of the most famous writers of the past century is on banned book lists,” Chute says.

Recommended by Hillary Chute

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel

“An incredibly moving book that captures the complexities of queer life in a very beautiful, but also very real way,” says Chute of the best-selling graphic memoir.

Recommended by Nikki Grimes

“It reflects the microaggressions Black people face daily, but in the least offensive way possible. If this is challenged, no book is safe,” Grimes says.

Recommended by Juno Dawson

“It’s so lyrical and beautiful, and as somebody who lived through the ’80s and ’90s, there were just floods of tears throughout,” says Dawson of the contemporary love story narrated by a chorus of gay men who died of AIDS.

This article appears in the October 2022 issue of ELLE.

Melissa Giannini is the features director of ELLE.

Source by www.elle.com