A discarded mask is seen on the floor inside New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport on Tuesday, a day after a federal judge in Florida struck down the CDC’s mask mandate for public transportation.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

A discarded mask is seen on the floor inside New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport on Tuesday, a day after a federal judge in Florida struck down the CDC’s mask mandate for public transportation.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

In a startling rebuke to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a federal judge in Florida on Monday struck down an agency order that required people nationwide to wear masks on public transportation to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

The travel mask mandate had been in place for 14 months, implemented shortly after President Biden’s inauguration, and was a key part of the country’s response to the pandemic. The decision strikes at the heart of the CDC’s mission.

In court documents, the judge described the order as “unlawful” and claimed “the Mask Mandate exceeds the CDC’s statutory authority.”

The news of the ruling was celebrated by some – videos of airline passengers ripping off their masks and rejoicing trended online.

But the decision against the CDC raised concerns in the public health community. It’s the latest in a series of challenges to the agency’s authorities that could hamstring its ability to respond to this pandemic and public health crises to come.

“It’s stunning, the extent to which the courts are reading federal statutes in the most cramped, narrow way possible to sharply limit the powers that the federal government can exercise now or in response to future emergencies,” says Lindsay Wiley, a health law professor at University of California, Los Angeles.

The CDC and Justice Department disagree with the mask ruling and are proceeding with an appeal. In the CDC’s assessment, “an order requiring masking in the indoor transportation corridor remains necessary for the public health,” the agency said in a statement. Further, “CDC believes this is a lawful order, well within CDC’s legal authority to protect public health.”

In the face of an unprecedented pandemic, the public health agency has flexed its regulatory powers to issue sweeping, legally binding orders that have affected travel, housing and migration. The agency is now facing a backlash over some of its actions from courts and Congress.

Limits on public health powers may be gaining popularity now, but health law experts say the moves are shortsighted; they warn that the restrictions could undercut the ability of health officials to respond effectively now and in the future.

Supreme Court slapdown on the eviction ban

If the reasoning behind this week’s travel mask mandate ruling was hazy, the Supreme Court decision last August on the CDC’s eviction moratorium was clear: in a 6-3 decision, the court found that the CDC had “exceeded its authority” in banning landlords across the country from ousting delinquent renters.

The rationale for the moratorium was that evictions could contribute to the spread of COVID-19 by making it harder for people to isolate or quarantine.

That the CDC put a stay on evictions in the first place was a move that surprised many, says Wiley. “I think the eviction moratorium really pushed the limits of what CDC is authorized to do,” she says, “Intuitively, a lot of the general public and a lot of federal judges felt that this isn’t exactly what CDC’s role should be – that it should be left to state and local governments to think about how to handle evictions during the pandemic.”

The Supreme Court’s majority opinion hammered home the point: “[T]he C.D.C. has imposed a nationwide moratorium on evictions in reliance on a decades-old statute that authorizes it to implement measures like fumigation and pest extermination,” it reads, “It strains credulity to believe that this statute grants the C.D.C. the sweeping authority that it asserts.”

The CDC’s regulatory powers stem from the Public Health Services Act of 1944 – “a very old statute that hasn’t been updated since,” says Larry Gostin, director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University. The law, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, predated the founding of the CDC by two years. It gave the public health branch of the federal government powers to, for instance, enforce quarantine laws.

Decades later, those legal powers are in need of an update: “There’s so much that has changed, but CDC’s powers haven’t,” Gostin says, citing world travel, mass migration and other factors that contribute to global disease spread.

The increasing conservatism of the courts also factored into the Supreme Court rebuke over the eviction moratorium, UCLA’s Wiley says. The stay on evictions, which was first issued in September 2020, “was upheld by federal courts when it was being defended by the Trump administration,” Wiley notes. It was only “when it was being defended by the Biden administration before a changing judiciary,” that court challenges started skewing against the government, and the Supreme Court struck it down, she says.

The Supreme Court decision set a precedent that may empower lower courts to further limit public health powers, says James Hodge, a health law professor at Arizona State University. It puts the CDC’s powers under a microscope, and opens it up to other challenges. “I think courts will take the [Supreme Court] decision and say things like, ‘It’s clear the Supreme Court does not envision [the CDC] having the direct federal authority to do what states should be doing,” he says. The decision was cited in the district court ruling this week that struck down the federal mask mandate.

It also forces the CDC to rethink its strategies as it faces other court challenges. “You get cold feet when you see what can happen to your scope and authority, when an entity like the Supreme Court gets hold of it,” Hodge says, “Especially in a more conservative court that … is issuing opinions that are about less about what’s in the public health interest, and more about agency authority.”

Other public health orders challenged

The CDC has issued some broad and far-reaching nationwide orders during the pandemic. Beyond issuing travel requirements and banning evictions, it has banned migrants at the borders and grounded the cruise industry for periods during the pandemic. These orders were punishable by fines and criminal penalties.

“This has been the largest and most expansive use of regulatory authority [by CDC], given the unprecedented nature of this pandemic threat,” Dr. Martin Cetron, director of the CDC’s division of global migration and quarantine, told NPR in March 2021, “While we’ve been reshaping and modernizing our public health authorities for decades – and we’ve used them in smaller ways, on an individual basis, in the past – this pandemic has called for the more broad, population-based use of public health authorities.”

The CDC did not make anyone available for comment for this story despite multiple requests.

While the CDC’s authorities from Congress haven’t changed in decades, there have been efforts by the CDC to more clearly define them, most recently with a set of rules, created at the tail end of the Obama administration that spelled out the CDC’s authority to detain and quarantine individuals that might be harboring dangerous infectious diseases.

“Those regulations were firmly entrenched pre-COVID,” says Arizona State’s Hodge, who serves as a regional director for the Network for Public Health Law. “Those rules are what CDC attempted to follow. But they got tripped up on political hurdles, and got into some hot water related to their breadth and scope.”

The cruise industry pushed back against a months-long “no-sail” order and the CDC’s long list of requirements for restarting, alleging unfair treatment from the agency. Immigration advocates railed against a CDC order under Title 42 that turned migrants away at U.S. land borders for the stated purpose of limiting the spread of COVID-19.

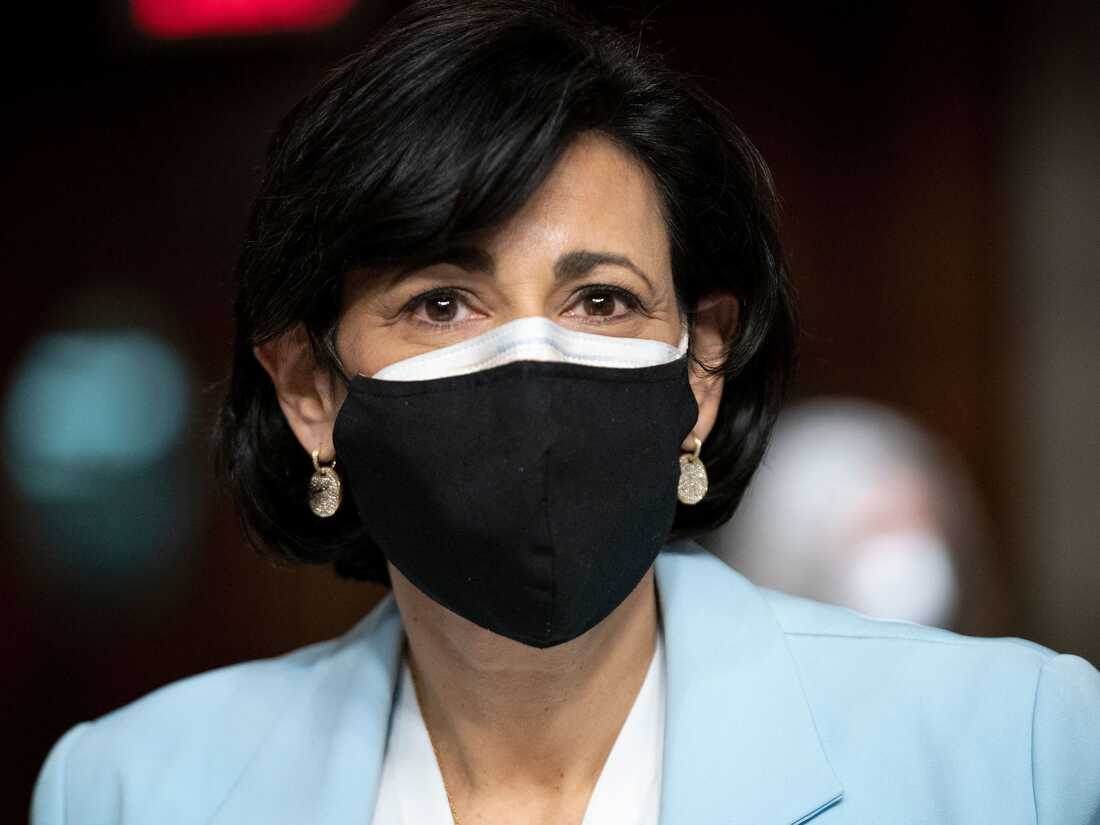

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Rochelle Walensky made the decision on April 1 to rescind immigration restrictions related to COVID-19 that were first implemented during the Trump administration.

Greg Nash/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Greg Nash/AFP via Getty Images

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Rochelle Walensky made the decision on April 1 to rescind immigration restrictions related to COVID-19 that were first implemented during the Trump administration.

Greg Nash/AFP via Getty Images

The CDC announced earlier this month that it’s winding down its Title 42 order – now set to expire May 23. The introduction of COVID-19 from migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border has “ceased to be a serious danger to the public health,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky wrote in the decision.

Health law experts say the public health rationale for establishing it in the first place was shaky, and made the agency appear politicized. “Recently, a judge said, I think quite rightly, ‘This has nothing to do with public health. This is just to do with politics and border policy,’ ” Georgetown’s Gostin says. While a ban on migrants may serve a president’s immigration policy goals, using public health rationale as political cover can weaken the agency, he says. “CDC must always act with evidence, and they must always show a scientific rationale for what they do – never a political one and never stretch beyond what CDC was designed to do, which is to protect the American public in ways that individual states can’t.”

Losing the bully pulpit

When the CDC’s travel masking order was invalidated by the federal judges in Florida, the agency was only able to recommend that travelers continue wearing masks.

When the agency issues advice – on masks, on testing, on quarantining and isolation – its guidance is routinely questioned and many states go on to craft their own policies.

As the CDC’s hard powers get challenged in court, the CDC’s soft powers – its ability to persuade through reputation and reason – have also taken a hit.

In the past, “CDC has never had national authority over what states do in public health, and yet we haven’t had the problems we’re having now,” Dr. William Foege, a former CDC director, said during a panel discussion this month. “If there was even an outbreak investigation, CDC had to be asked by the state or a county or a city or a tribe to do that investigation … and yet the system worked so well that it was never a problem. We didn’t need more authority.”

Previously, states took CDC guidance as a basis to regulate. “Even though CDC wasn’t passing the laws, the fact that the CDC said, ‘this is what we think people should do’ carried a lot of weight,” says Liza Vertinsky, a health law professor at Emory University.

But the agency’s reputation has been tarnished by perceptions of politicization during the pandemic. The CDC has lost public confidence and trust, and its guidance is now frequently treated as a suggestion by some states and as a trigger for active opposition by others. “I think they can do less than they should be able to do,” Vertinsky says of the CDC, “because when they issue the guidance, it no longer carries the weight.”

Limits on public health powers have risks

The conundrum for public health officials, tasked with navigating a pandemic while their powers and popularity wane, extends to state and local authorities. Some legislatures are limiting the scope and duration of public health orders on masking, vaccinations and gatherings, and requiring more public and political input for disease mitigation measures.

“There’s no question that the nation’s public health authorities are being challenged at all levels,” says Dr. Georges Benjamin, head of the American Public Health Association. “We are tying the hands of our nation’s public health officials, and we need to stop and think about that because you cannot manage an emergency by committee.”

The move to curb so many public health powers strikes some as myopic. “People on all parts of the political spectrum need to understand that the next pandemic might look very different,” says Wendy Parmet, health law professor at Northeastern University, “What if the next disease kills kids, not adults? Are we going to force kids to go to school in person?”

In the next pandemic, the political dynamics could be flipped. Republicans might prefer to be more aggressive at disease control than Democrats, as happened with the Ebola outbreak in 2014, when “Republicans [wanted] more quarantines, and Democrats were arguing for a much more lenient approach,” Parmet says. “We need to prepare for the unknown. We need to have the imagination to understand that what comes next might not look either epidemiologically or politically like what we’ve seen.”

The CDC must “tread carefully” as it determines how to respond to court challenges to its powers, Arizona State’s Hodge says. The agency has asked the Justice Department to appeal this week’s travel mask mandate ruling, to help preserve the agency’s public health authorities.

There are big benefits to winning an appeal – and clear risks to losing. Currently, the district court ruling is a limited decision with “very little precedential value,” Hodge says. A failed appeal in a higher court could put permanent limits on the CDC’s regulatory powers.

For the future, the CDC’s authorities should be clearly defined, Georgetown’s Gostin says. “The CDC needs to have power, so it doesn’t always have to look behind its shoulder at what some governor, some congressperson, or some judge is saying. They need to act decisively and flexibly,” he says. “But they also need to respect individual liberty and act with evidence and always act using the least restrictive alternative.”

He says these principles, stretched and magnified by COVID-19, should be assigned to the agency as part of a modernization act from Congress, which hasn’t significantly updated the CDC’s powers since 1944. “We need to make sure that they have the kind of modern legal tools that any public health agency needs to do a good job.”

But in the current political climate, when public health mandates are unpopular and public health workers are facing attacks, “it’s just as likely CDC would be curtailed as expanded” as part of a congressional reexamination of its powers, Gostin says.

By all accounts, including its own, the CDC has acted imperfectly in its response to this pandemic. The agency has much work ahead in evaluating how it could do better and how to regain public trust.

Even so, the push to restrain the CDC’s regulatory powers is misguided, and could lead to dangerous repercussions, Hodge warns. “When the next threat hits us, everybody is going to turn right back to CDC and say, ‘What are you doing about this? How are you responding?’ ”

Having less authority to issue orders to contain health threats could backfire on the nation.

Source by www.npr.org